Aquatic scientific names in the news …

29th March.

Invasive Species Week

As 27 March – 2 April is Invasive Species Week 2017 in the UK I thought I’d take a look at the etymology of a few of the more important aquatic invasive species.

Invasive species week is an initiative of the Non-native Species Secretariat (NNSS) and the Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) with the aim of raising awareness about invasive species in the UK.

Among the invasive species listed on the NNNS website there are 39 aquatic, semi-aquatic, or aquatic associated species, these range from fairly large mammals such as the Chinese Water Deer and American Mink, through a number of aquatic associated birds, various amphibians, numerous aquatic plants and seaweeds, and invertebrates including crustacea and molluscs

Non-native species are plant or animal species that are found outside of their natural past or present distribution (introduced species). The term ‘non-native species’ is the equivalent of ‘alien species’ as used by the Convention on Biological Diversity. Generally speaking It refers to species and subspecies introduced through human action, “hitchhiking”, or other means.

An invasive non-native species is any non-native animal or plant that has the ability or potential to spread to a degree that might cause damage to the environment, the economy, our health and the way we live, or reduce biodiversity.

At the time of writing there seems to be a disappointingly poor coverage of this story by the media with only the Guardian reporting on it in any depth.

It’s difficult to tell from the NNSS website which species are of most concern, so for this exercise I’ve chosen to use the species listed under the NNSS species alerts issued as part of the GB rapid response protocol. All these species have been found in the UK and are of obvious concern.

Water Primrose – Ludwigia grandiflora

An invasive non-native plant from South America which has become a serious pest in other countries, including France, where it smothers water bodies reducing the numbers of native species and potentially increasing the risk of flooding.

Etymology.

Ludwigia – Eponym, honouring Christian Gottlieb Ludwig (1709-1773); genus named by Carl Linnaeus

grandiflora – Latin, grandi-, grandis, large, great; -flora, the goddess of flowers; grandiflora, with large flowers

Quagga Mussel – Dreissena rostriformis bugensis

A highly invasive non-native freshwater mussel from the Ponto-Caspian region, very similar to Zebra Mussel. It can significantly alter whole ecosystems by filtering out large quantities of nutrients and is also a serious biofouling risk blocking pipes smothering boat hulls and other structures.

Etymology.

Dreissena bugensis (Andrusov, 1897)

Dreissena – Eponym, honouring M. Driessens, a pharmacist at Mazeyk, from whom Van Beneden, had received a consignment of live molluscs

bugensis – etymology unknown, -ensis, indicates name is a toponym

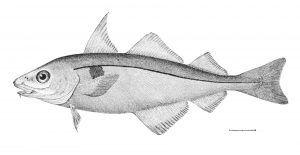

“Killer shrimps” – D. haemobaphes and D. villosus

Invasive non-native freshwater gammarid crustaceans that have spread from the Ponto-Caspian Region of Eastern Europe. They are both voracious predators that kill a range of native species, including young fish, and can significantly alter ecosystems.

Dikerogammarus villosus (Sowinsky, 1894)

Etymology.

Dikerogammarus, – Greek, Di-, di (δι), two; -kero-, keras, horn; -gammarus, kammaros (καμμαρος), lobster

villosus, Latin, hairy, shaggy, rough

Dikerogammarus haemobaphes (Eichwald, 1841)

(No image available)

Etymology.

Dikerogammarus, – Greek, Di-, di (δι), two; -kero-, keras, horn; -gammarus, kammaros (καμμαρος), lobster

haemobaphes, -Greek, haemo-, haima (αιμα), blood-red; -baphes (βαφη), a dipping in dye, dyeing, dye

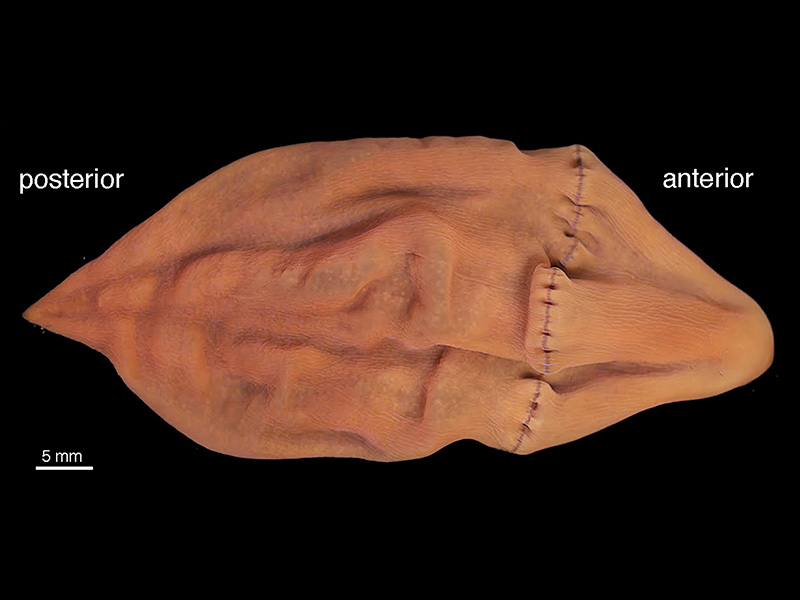

Carpet Sea-squirt – Didemnum vexillum (Kott, 2002)

Thought to be originally from Japan, it has become a pest in other countries by smothering native species and interfering with fishing, aquaculture and other activities. It has recently been found in some marinas in England and Wales and there are strong concerns that it will spread more widely.

Etymology.

Didemnum, Greek, Di-, di (δι), two; -demnum (δεμνιον), bedstead, mattress, bed, bedding;

vexillum, Latin, a military ensign, standard, banner, flag.

Sightings of any of these species should be reported through either the appropriate reporting page on the NNSS website or by email with a photograph and location details to: alertnonnative@ceh.ac.uk

All images courtesy of www.cabi.org/isc