Aquatic scientific names in the news …

Two species of fish, an Anglerfish, Lasiognathus dinema, and a Seadragon, Phyllopteryx dewysea, feature in this year’s ESF Top 10 New Species list.

The list, an annual event established in 2008, is compiled by ESF’s International Institute for Species Exploration and comprises the Top 10 species from among the thousands of new species named during the previous year, selected by an international committee of taxonomists and calls attention to the fact that new discoveries are being made even as species are going extinct faster than they are being identified.

The list is published around May 23 each year to coincide with the birthday of Carolus Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy.

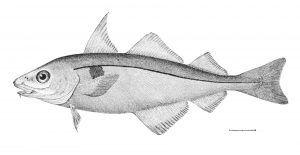

Lasiognathus dinema Pietsch & Sutton, 2015

Image: Theodore W. Pietsch, University of Washington

Image: Theodore W. Pietsch, University of Washington

Discovered during a Natural Resource Damage Assessment conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. A small deep sea species of Wolftrap angler (1,000 to 1,500 metres, around 5cms in length) with a prominent esca. Different species of anglerfish can be distinguished visually by the details of a structure called an esca (Latin, food, bait) that projects over their heads like a fishing rod and is believed to act as a lure to attract prey. This organ is located at the tip of a highly modified, elongated dorsal ray, in some species the esca is home to symbiotic bacteria that are bioluminescent, producing light (a rare commodity in the depths of the ocean) and is presumed to aid in the attraction of prey.

Etymology

Lasiognathus – Greek, Lasio-, lasios (λασιος) , shaggy, wooly, hairy; -gnathus, gnathos (γναθος), jaw. Alluding to the huge number of long teeth of the upper jaw

dinema – Greek, di- (δι), two; -nema, nhma (νημα), that which is spun, thread, filament; referring to two thread-like prolongations arising from base of escal hooks.

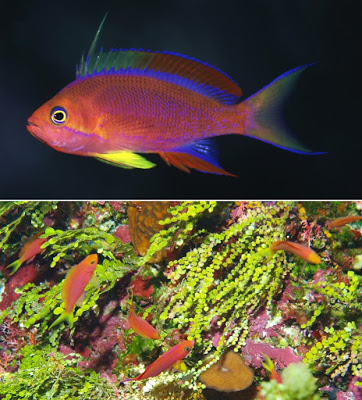

Phyllopteryx dewysea Stiller, Wilson, & Rouse, 2015 – Ruby seadragon

Image: Western Australian Museum

Image: Western Australian Museum

Only the third known species of seadragon, and the first to be discovered in 150 years, possibly because it lives in slightly deeper waters than its relatives. A relatively large species, around 24 cms in length, it has rarely been previously encountered; the coloration suggests it lives in deeper waters than other seadragons since red shading would be absorbed at depth, effectively serving as camouflage.

Etymology

Phyllopteryx – Greek, Phyllo–, phyhllon (φυλλον), leaf; -pteryx, pteruc (πτερυξ), wing, fin. Alluding to the small leaf-like appendages of the first named member of the genus, the Common or Weedy Seadragon.

dewysea – Latinized name, honouring, “… Mary ‘Dewy’ Lowe, for her love of the sea and her support of seadragon conservation and research, without which this new species would not have been discovered.” Of the Lowe Family Foundation.

Ref. A spectacular new species of seadragon (Syngnathidae) Josefin Stiller, Nerida G. Wilson, Greg W. Rouse. Royal Society Open Science 2015

Pseudanthias tequila, Image: N. Tsuji.

Pseudanthias tequila, Image: N. Tsuji.