Aquatic scientific names in the news …

A species of freshwater stingray, Potamotrygon rex, a swimming centipede Scolopendra cataracta, and a marine worm Xenoturbella churro, all feature in this year’s ESF Top 10 New Species list.

The list, an annual event established in 2008, is compiled by ESF’s International Institute for Species Exploration and comprises the Top 10 species from among the thousands of new species named during the previous year, selected by an international committee of taxonomists and calls attention to the fact that new discoveries are being made even as species are going extinct faster than they are being identified.

The list is published around May 23 each year to coincide with the birthday of Carolus Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy.

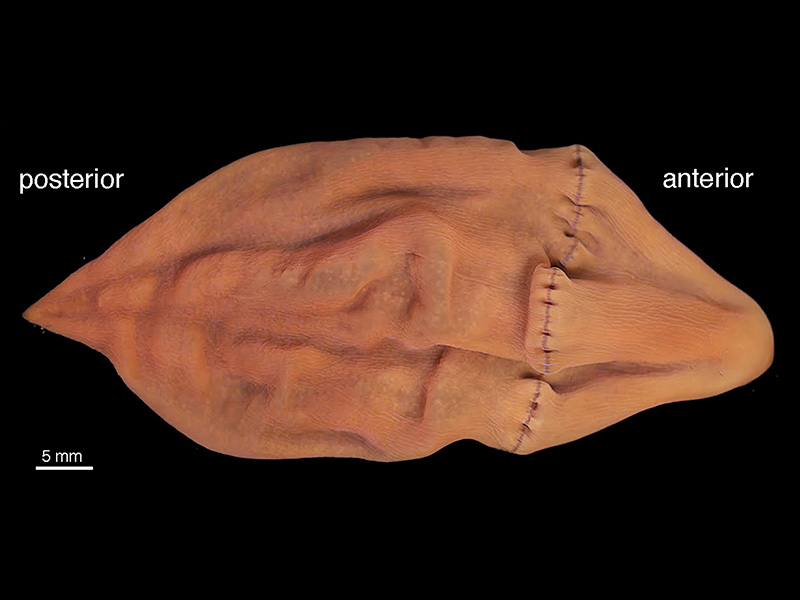

Potamotrygon rex Carvalho 2016

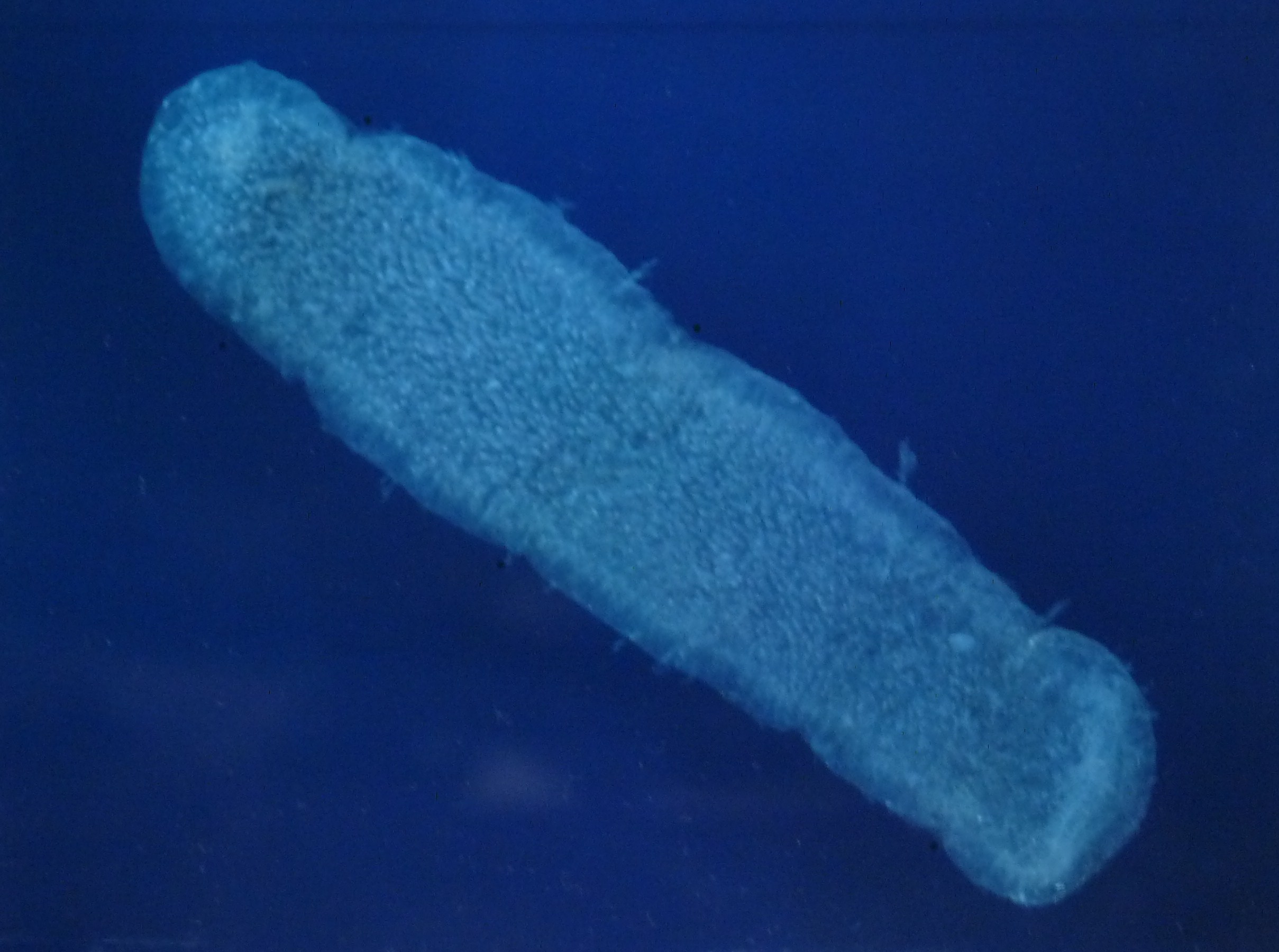

Dorsal view of juvenile specimen

Dorsal view of juvenile specimen

Image: Marcelo R. de Carvalho

This large, strikingly patterned freshwater stingray is endemic to the Tocantins River in Brazil and is among the 35 percent of the 350 documented fish species in the Tocantins River that are found nowhere else on Earth. The type specimen is 1,110 mm in length. Large specimens may weigh up to 20 kg.

The stingray has a blackish to blackish-brown background colour, with intense yellow to orange spots that, combined with its size, earn it the title “king.” The discovery of such a large and brightly coloured ray highlights how incompletely we know fishes of the Neotropics.

Etymology

Potamotrygon – Greek, Potamo-, potamos (ποταμος), river, stream; Latin, –trygon, (Greek τρυγων) a stingray.

rex – Latin, absolute monarch, king – named for its large size and striking color pattern

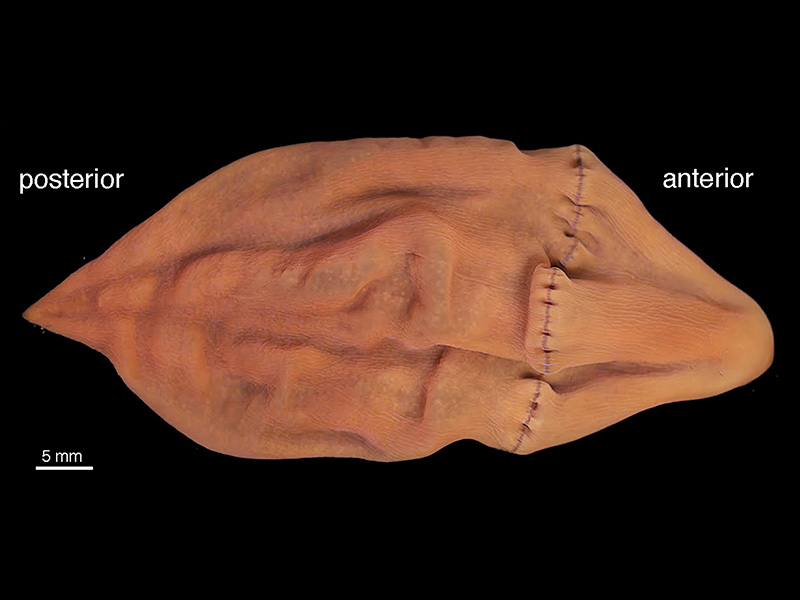

Scolopendra cataracta Siriwut, Edgecombe & Panha, 2016 – Waterfall Centipede or Swimming Centipede

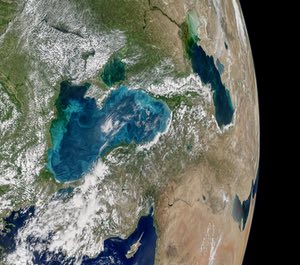

The largest reported centipede, with a maximum recorded body length of around 20 cm.

The largest reported centipede, with a maximum recorded body length of around 20 cm.

Image: Siriwut, Edgecombe and Panha

This new centipede is black, has 20 pairs of legs and is up to 20 cm in length. It is the first species of centipede ever observed to be able to plunge into water and both run along the stream bed, in much the same manner as on dry land, and swim with eel-like horizontal undulations of its body. It would appear to have a hydrophobic surface as out of water, water rolls off the centipede’s body leaving it totally dry.

The species, with its surprisingly adept swimming and diving abilities, was discovered under a rock but escaped into a stream where it rapidly ran to and hid under a submerged rock. A member of the predominant centipede genus in tropical regions, the centipede’s amphibious ability is unprecedented. Its population status is of concern because of habitat destruction, including tourist activities, along streams and river embankments where the new species is found.

Etymology

Scolopendra – Latin, (Greek σκολοπενδρα), a kind of multipede, millepede.

cataracta – Latin, a waterfall. Named for the Tad E-tu Waterfall where the type was collected

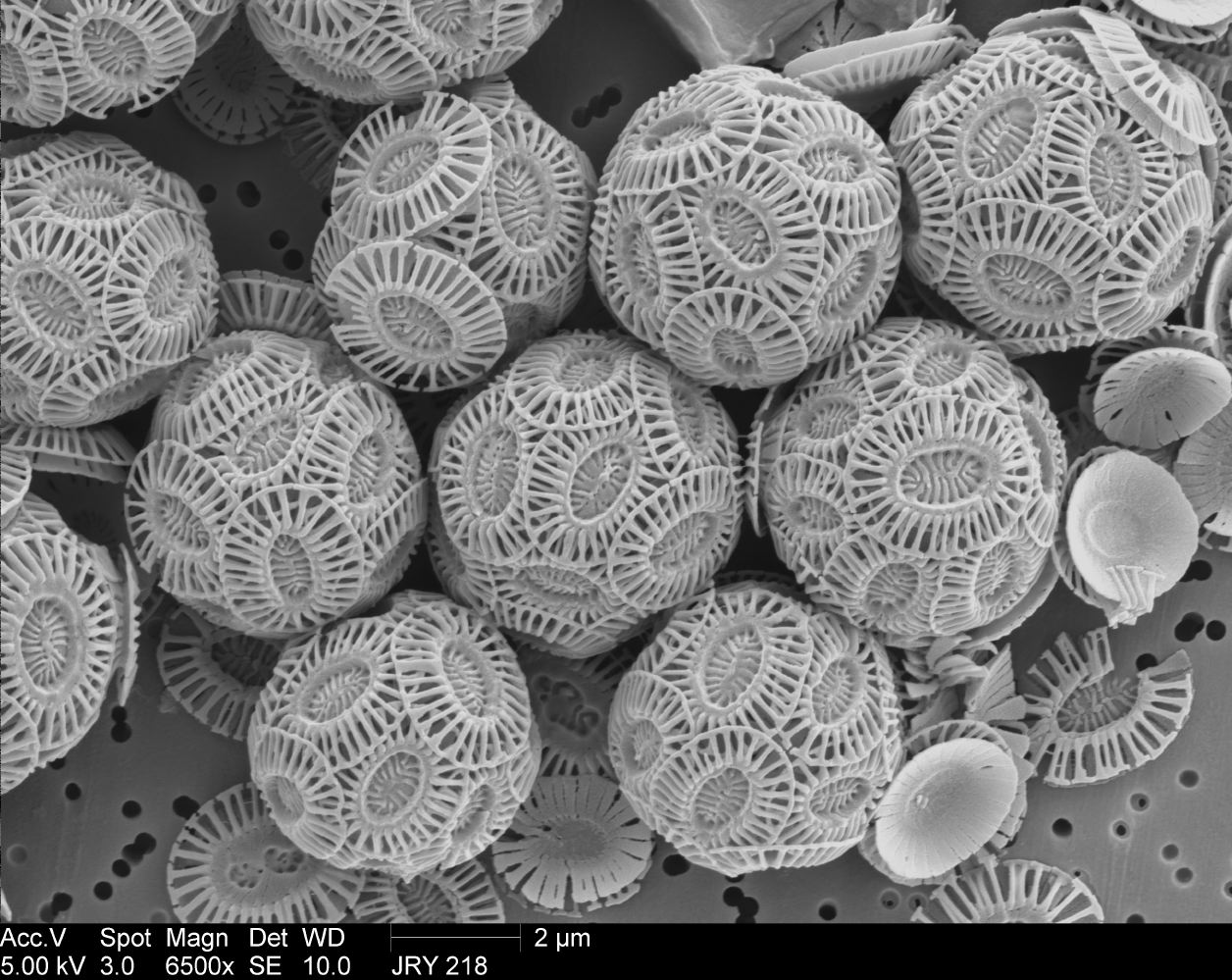

Xenoturbella churro Rouse, Wilson, Carvajal & Vrijenhoek, 2016

Discovered deep in the Gulf of California, 1,722 meters below the surface, Xenoturbella churro is a 10 cm-long marine worm, one of half a dozen species now known in the genus. It is representative of a group of primitive worm-like animals that are the earliest branch in the family tree of bilaterally symmetrical animals, including insects and humans. Like some of its relatives it’s believed to feed upon mollusks, such as clams. Curiously, much like coelenterates (corals, anemones, etc.) they have a mouth, but no anus.

Dorsal view. Image: Greg Rouse

Dorsal view. Image: Greg Rouse

Etymology

Xenoturbella – Greek, Xeno-, xenos (ξενος), a guest, stranger, foreigner; foreign, strange; Latin turbella a little crowd, a bustle, stir, diminutive of turba crowd – referring to the cilia which produce minute whirls in the water.

churro – Spanish, a type of fried pastry. The new species is uniformly orange-pink in color with four deep longitudinal furrows that reminded the authors of a churro, a fried-dough pastry popular in Spain and Latin America.

See also: ESF Top 10 New Species list 2016

Marianne Nyegaard with a beached hoodwinker sunfish. Image: Murdoch University

Marianne Nyegaard with a beached hoodwinker sunfish. Image: Murdoch University H

H

Image: National Museums Northern Ireland

Image: National Museums Northern Ireland